Fig. 1 The world of "minimal data" 4

I asked my grandson the price of a postage stamp in binary, and pretty quickly he reported the result, 10100101 (pennies). And how many bytes is that? One byte.

Then we did an internet search for "price of first-class postage stamp" and we got "about 6,420,000 results". Many of the websites display a huge amount of colour and artistic design, requiring megabytes of data even for a static image, to say nothing of the bandwidth and the electrical power required to transmit that data. All this seems to suggest extreme inefficiency of information transmission via the internet, since the required information needs only one byte.

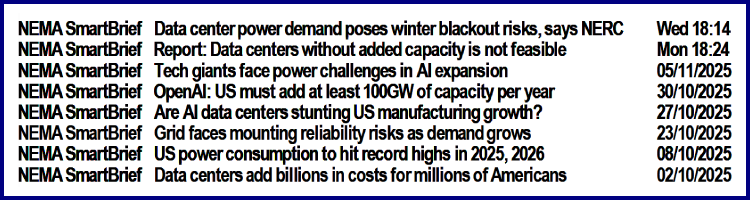

The increase in data processing is well known, although it might be difficult for the average person to estimate the quantities involved. Quantities of what? Bytes? Terabytes? Zettabytes? Yottabytes? 1 It’s even questionable whether the mere counting of bytes is a satisfactory way to quantify useful information, or know-how, or savoir faire, or wisdom. But what might be more intelligible to anyone who reads e-mails or newspapers is the list of e-mail titles in Fig. 2, taken from my own in-box, showing regular and frequent alarms raised by NEMA2 about the impact that AI and data centres are having on the demand for electricity. No kidding : data centres represent the largest single source of increased demand for electrical power.

There was a time (no so long ago) when electrical engineering was divided into two categories : heavy current and light current. Heavy current meant motors, generators, power stations, transformers, switchgear, overhead lines, and currents measured in [A] or [kA]. Light current included electronics, signal processing, computing, and communications, and currents measured in [mA] or [μA]. Evidently the current that is demanded by data processing is no longer "light". It has become extremely heavy — according to NEMA, the application with the greatest growth in demand for heavy amperes. Have we turned the world on its head?

Fig. 2 NEMA announces the effect of data centres on the demand for electrical power

Let’s get back to the particular role of electromagnetic analysis and the design of electromagnetic equipment. Are we contributing to this bizarre situation?

My answer is definitely not.

It’s true that numerical analysis involves a lot of data (see Engineer’s Diary No. 87), with millions of elements and numbers expressed in lots of bytes, and all this data is constantly transforming itself in such processes as transient analysis and optimization, with extensive use of computer graphics requiring ever more memory and storage. But most of this data is transient, evanescent, temporary — not needed in the long term. It exists fleetingly in a series of steps along the way to a final design that can be defined in terms of a much smaller dataset. Most of it does not need to be kept.

How small is that final dataset? How many megabytes of data are required to completely define a product such as an electric motor?

The answer is not easy to define precisely, because the amount of data needed for one electric motor design will differ greatly between different applications and different manufacturers. But think of it in a historical context. The open book in Fig. 1 shows dozens of drawings of an electric machine from about 1900. No more than a few of these drawings were sufficient to define some large and sophisticated machines in their day, including the largest generators in the world. The quantity of data in these drawings is minuscule by modern standards — probably a few kB at most, in digital terms.

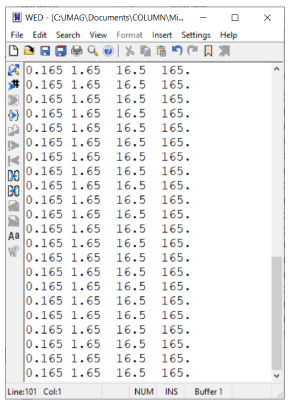

The size of dataset required for a design calculation sheet can be estimated simply enough with reference to Fig. 3, which shows a screenshot of part of a text file containing 100 lines, each line having four numbers displayed with three significant figures. Scale your calculation sheet from this! The text file size is 2.53 kB and that of the screenshot (png file) is 133 kB. Taking two 8-bit bytes for each of the 400 numbers, the actual data requires only 800 bytes, less than 1 kB. Of course this example is extreme: but it makes the point! Note the extreme inefficiency of representing this data in a graphic image: it requires more than 100 times the storage than the useful actual data itself.

Fig. 3 A simple text file

Moving forwards from there to the early days of computer-aided engineering in electric machine design, my PhD supervisor3 more than once posited that an electric machine design was "quite a complicated problem, with as many as 100 parameters". As students we marvelled at such complexity, and the overwhelming challenge of handling (let alone optimizing) such a large inhomogeneous dataset. And although these numbers seem quaint today in their smallness, the fact remains that the quantity of data required to define and characterize a machine design is much less than the quantity of data required transiently in the process of evolving that design through numerical analysis and optimization. So it seems unlikely that whole data centres will be needed to store our machine designs.

Taking a completely different point of view, it is probable that more than 90% of all generated electricity worldwide comes from rotating machines (including steam-turbines in thermal and nuclear power stations, hydro-electric generators, wind turbines, diesel generators, and others using wave power and other types of water-turbines). If the growth in demand is as big as NEMA says it is, what this means is that there’s going to be plenty of work in electric machine design, analysis, and optimization. This includes the work of integration of all these different types of generators into power systems that are becoming ever more diverse and complex. It will require a lot of data — but not necessarily to store the details of traditional electromagnetic components.

A wider perspective on the future of big data in electrical engineering may be gleaned from this quotation from the guest editorial in the special edition on Virtual Power Plants in the IEEE’s Power & Energy Magazine5 :

So while instances of "minimal data" may retain a useful role for some time into the future, it seems that big data will eclipse it, if it hasn’t already done so.

Notes

1 https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/computer-science-fundamentals/understanding-file-sizes-bytes-kb-mb-gb-tb-pb-eb-zb-yb/

2 National Electrical Manufacturers’ Association (USA)

3 The late P.J. Lawrenson, F.R.S.

4 The old book in Fig. 1 is S.P. Thompson, Design of Dynamos, E. & F.N. Spon Ltd., 1903

5 Guest Editorial on Virtual Power Plants, IEEE Power & Energy Magazine, Vol. 23, No. 6, November/December 2025, p. 31