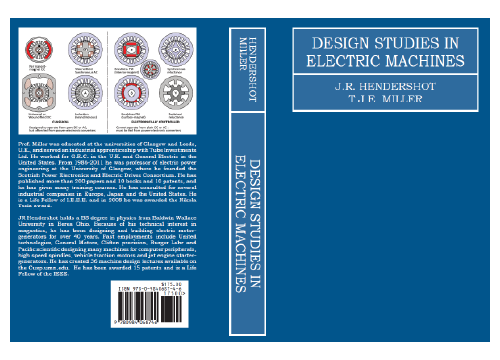

Fig. 1 Mindful processing

There is a curious parallel between a live musical performance and a large engineering computation involving Big Data (Engineer’s Diary No. 87). Of both activities we can make the same observations:

-

The stakes are high.

-

We must train and prepare to get it right first time.

-

If / when errors arise, we must ride through them without detriment to the overall process.

In music the tension associated with a public performance may be extremely high; but the same is true in engineering analysis. There is a critical audience of paying customers, as well as one’s own colleagues (as in the orchestra) who depend on one’s results. In the engineering environment, getting it right first time is obviously dependent on technical proficiency; but this is often not guaranteed, and every day we hear of new engineering failures (only the most catastrophic of which appear in the headlines).

Engineers are of course familiar with learning from mistakes, but we tend to regard that as no more than a good habit or a vague general principle. There is, however, a school in music-training that systematizes the process of learning from mistakes. 1 We can ask whether this can be achieved in engineering. Let’s think about that in the particular case of engineering analysis (which encompasses all stages of engineering calculations and forms the basis of synthesis or design, which we can liken to the public performance of the music).

Fig. 1 tries to formulate graphically some of the principles taught by applied cognitive science in this process. 2 Think of your next big finite-element calculation as a musical performance, in relation to the structure of the chart. To make it work, one has to use one’s imagination to see the parallels between practising for a concert and preparing a big computation. I would say these parallels are surprisingly close.

Before we dive into Fig. 1, let me say that it represents only a tiny subset of what musicians do with cognitive science, and cognitive science undoubtedly goes well beyond what is done in music. But it’s a start, and I would argue that it can also be applied to the process of teaching and studying engineering as well as practising it.

The diagram is in two parts. At the bottom we see an uninterrupted sequence of mindless repetitions of a certain process, A. The shallow upward gradient represents the slow rate of progress. Mindlessness is reflected in the monotonous uniformity of the A-blocks. While tedious repetition of certain tasks is inevitable in engineering, it does not have to characterize the entire process. It can be brightened up, and made more efficient at the same time.

In the top diagram the overall process is separated into three distinct segments, 1,2 and 3. Process A receives attention in segments 1 and 3, while a different process B receives attention in segment 2. The subdivision is what the musicians call “chunking”, while the alternation between processes A and B is what they call “interleaving”. In music practice the objective is secure learning, while in engineering a similar concept of secure foundations applies. In both cases efficiency is important (avoiding wasteful repetition), and so is the overall rate of progress, which is reflected in the overall gradient in the top diagram. Of course the sequence need not be limited to three segments, and the very act of subdivision introduces intervals that may be useful or even necessary for other purposes. Cognitive science seizes on the value of such intervals, which the musicians call “spacing”. They constantly pay attention to the length and frequency of intervals in their practice, in much the same way as process engineers optimize the flow of processes in and around the factory.

Within each segment in the top diagram we have replaced the mindless repetition with a rather more detailed structure. Labels A and B cover the widest possible range of practice methods or processes; but in segment 1 we see another idea that can perhaps be described as “fragmentation” or “subdivision”. 3 In this case we are still working on practice activity A, but it is subdivided into short segments labelled a — lower-case for small ! — and in piano practice these small segments are recommended to be short enough and slow enough to be played without mistakes, [1,2]. The a-segments are to be repeated, say, three to five times, then take a break of 10 seconds or so, then repeat a second series of a-segments, then a second break, then a third series of a’s. In the diagram, the breaks are denoted by the dashed lines.

What strikes me about the fragmented or subdivided pattern is that it is similar to how I do simple engineering calculations, especially in the early stages of designing a machine. The individual calculations are short and simple, but there are several of them, and they tend to interfere with each other. Repetition of these is perfectly natural and traditional.

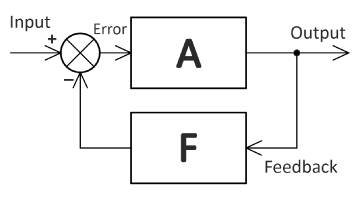

Fig. 2 Classical feedback principle

It may even be the reason why engineers’ pencils always have erasers at the end. We may laugh, but we’re talking about an iterative solution to a non-linear problem with many variables. And manual methods often precede the heavyweight computer methods — especially in the concept-forming or “sizing” phase of a design project — and they have to be done slowly enough and carefully enough to make sure they’re right.

The fragmentation principle — or some variant of it — is one that I would like to try in teaching undergraduate engineers, and it would have appealed to me when I was a student myself. Undergraduates in my experience always love examples, both worked examples and problems, and the keen ones will sometimes work through all the examples in the textbook, even though there may be quite a bit of repetition. There are even serious undergraduate textbooks based on this principle, [4–6]. It’s not “drilling” and it’s certainly not “rote learning”. It’s cognitive science!

Each of the segments in Fig. 1 is represented as a classical feedback loop. The standard form of this is reproduced in Fig. 2, and it will be familiar to electrical engineers in terms of the processing of electrical signals, especially in control theory. In that context the signal paths carry numerical data, either analog or digital; but here we will generalise the idea to represent any relevant information connected with the process. Thus in music the practice activity is labelled A, and this could represent any form of focussed practice (including 3-break-3). The result of each session is labelled Output, but there is also an Input which is the goal or objective that is set at the start of each segment (or at the start of the entire process). The general intention in practising is to make the Output equal to the Input: in other words, to achieve precisely the desired goal for that practice session. The process from Input through to Output is called the feedforward path or process, and it is nothing more or less than the practice process A.

To make the Output follow the Input more closely — in other words, to make the practice result closer to the practice goal — we introduce a feedback path F. What this does is to take the Output back to the Input and compare them. That’s the function of the circle with the X, which is called a summing junction. Note that the Feedback is subtracted from the Input because we want to work with the Error: that is, the difference between our result and our goal. If the result is equal to the goal, the error is zero, and so the practice process A has nothing to work on, nothing to do. Perfection achieved!

The process works better, the more effective the practice process A. 4 Thus the system is not a substitute for good practice methods. But in comparing the result with the goal (the Output with the Input) what it does is to steer the practice towards a zero-Error condition. In other words, it tends to eliminate practice errors that would otherwise result in a deviation between the result and the goal. It makes practice inherently more efficient, and avoids wasted time and effort.

The feedback process F need not be a simple return of the Output to the Input. It can be filtered, and this is what the teacher is doing when s/he identifies precisely the characteristics of the Output that need to be compared with the Input. In an electronic circuit the data in each of the paths is essentially numerical, but in a musical performance it is obviously much more complex, with many attributes that require a whole language to describe them. But the feedback principle still applies. The teacher will, of course, also advise and prescribe the feed-forward process A: that is, the practice methods themselves. Both functions can in principle be executed by the student himself or herself: for a beginner, that might be a case of doing things the hard way (self-learning), but for a seasoned musician it is almost certainly a well-developed part of his or her skill-set. 5,6

The overall rate of progress is represented by the average gradient resulting from the steps that we can see after each of the breaks, and it is clearly steeper than the bottom graph of mindless repetition.

Is the feedback process applicable to engineering calculations? Can it be programmed into analysis and design software? Both questions are answered with a resounding “yes”, and it may be of interest for readers to analyse the structure of their calculations in terms of a diagram such as Fig. 1, with its simpler element Fig. 2.

Notes

1 Similar practices are to be found in other activities such as sports, and indeed anywhere cognitive science is applied to improve training and performance. (See [2,3])

2 Fig. 1 was constructed directly as a summary of some of the teachings in [1 & 2].

3 The terms “three-break-three” and “microbreaks” have been used to teach the value of this structured fragmentation in music [1], with detailed justification from cognitive science [2].

4 In engineering parlance, A is (felicitously in this context) termed the gain. It is simple to prove that high gain reduces the error, but excessive gain can lead to instability and oscillations. Draw your own musical analogy!

5 Musicians describe the feedback process in their own language, which is generally broader in scope than the engineering definition used here. A diagram tends to make the description appear to be narrowly constrained, and in many engineering contexts it is narrowly constrained; but the general idea is surely common to both disciplines and is used much more widely.

6 Interesting thought: delivering A to the student is lecturing; delivering A + F to the student is teaching.

References

1. Search: Piano with Rebecca B, YouTube video Practice Less, Improve More, May 29, 2025

2. Molly Gebrian, Learn Faster, Perform Better, A Musician’s Guide to the Neuroscience of Practicing, Oxford University Press, 2024.

3. Weinstein Y., Madan C.R., Sumeracki M.A., Teaching the Science of Learning, Springer; Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications (2018) 3:2 DOI 10.1186/s41235-017-0087-y

4. Nasar, Syed A., Theory and Problems of Electric Machines and Electromechanics, Schaum’s Outline Series, McGraw-Hill, 1981

5. Nasar, Syed A., Theory and Problems of Electric Power Systems, Schaum’s Outline Series, McGraw-Hill, 1990

6. Murray R. Spiegel, Theory and Problems of Vector Analysis, Schaum’s Outline Series, Schaum Publishing Company, N.Y., 1959